"You are standing in an open field ..."

Back in the day, childhood favorites were like childhood friends: proximity was everything. I didn’t know it then, but these games were teaching me a way of thinking about play that I’d recognize decades later at the table. Infocom games might not have objectively been the best, but they were available, and they've held up much better than I could have hoped.

They had a lot to live up to after all these years. These weren't just games I booted up when dysentery wiped my party in Oregon Trail, or when I dead-ended in Where in the World is Carmen Sandiego. These were places I returned to, over and over, until they became familiar. I read more carefully, talked through puzzles with my dad, and stumbled onto a sense of humor that still annoys my wife on a daily basis.

In interactive fiction (née “text adventures”), the game is the referee. It describes the world and presents obstacles to overcome—almost always puzzles; even “combat” was treated as a puzzle [[footnote: With Beyond Zork being the one exception to this, which I think this was a misstep: Once the player solves the puzzle (i.e. employs an item to make an enemy vulnerable), making them spam attacks perfunctorily to whittle down this thing's HP is kind of lame.]]. You interpret those descriptions and input your chosen action, which the game adjudicates [[footnote: Or rejects outright if the verb isn't recognized or the parser chokes.]]. It's the same core gameplay loop as most TTRPGs, filtered through the extreme technical limitations of Reagan-era personal computers. Those limitations came in the form of the small set of verbs (look, examine, open, take, put, etc.), a handful of prepositions, and the items made available by the Implementors [[footnote: It reminds me of the OSR compared to modern D&D: solutions derived from character limitations smacking against player creativity, versus solutions selected from a massive toolbox of character options. Players in either can choose to engage with the game through "role-playing," but at least in OSR the play loop is an adventure game.]].

"... west of a white house, with a boarded front door."

My dad was a blue-collar gearhead in the '80s. We were solidly lower middle-class, but he loved his hi-fi audio system, his home video setup, and his Apple computer. I've never asked him why he chose the much more expensive Apple IIe (and later IIgs) over Commodore, or an early IBM clone, but I'm glad he made the choice he did [[footnote: I got an answer out of him: It turns out he didn't think much of the quality of Commodores, and IBM clones were too business-oriented. Apple computers were cool. The more things change...]].

We spent hours playing these games. The experience introduced me to the idea of structured play in a shared imaginary space. I'll never know the extent to which he was humoring me, but we would talk about the rooms and he'd make sure I understood the descriptions. He'd try my suggestions for whatever obstacles we faced, even if doing the wrong thing meant likely running out of lantern oil and being eaten by a grue. The games were designed with just one protagonist, but when we played together I imagined navigating them as a duo.

"There is a small mailbox here."

The games were tiny by modern standards, so they needed to trim every ounce of fat. The earliest were limited to roughly 80KB, and the largest only ever reached ~256KB. In other words, the total size of the Zork Trilogy, plus Beyond Zork, is (considerably) less than half the size of the images on this page.

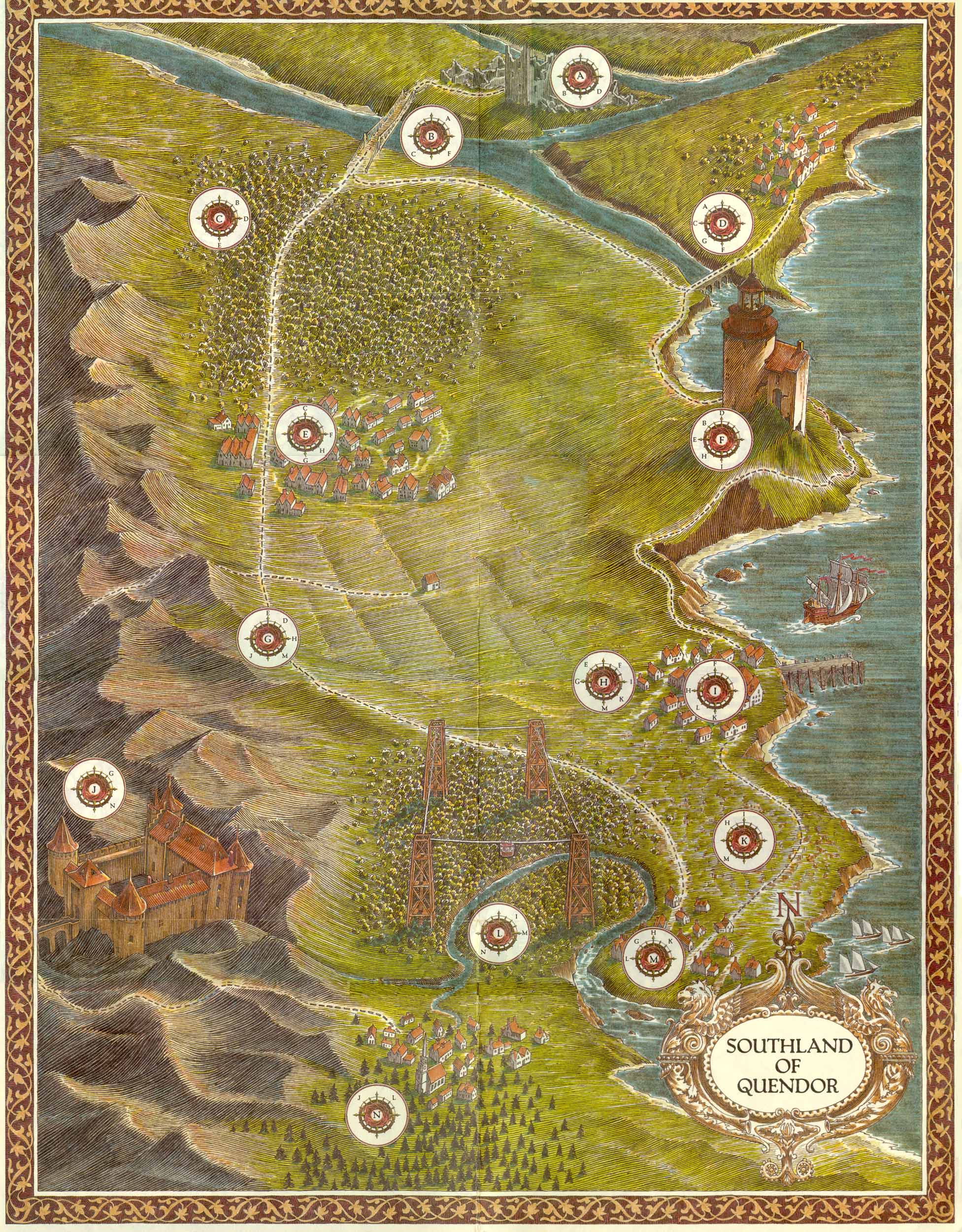

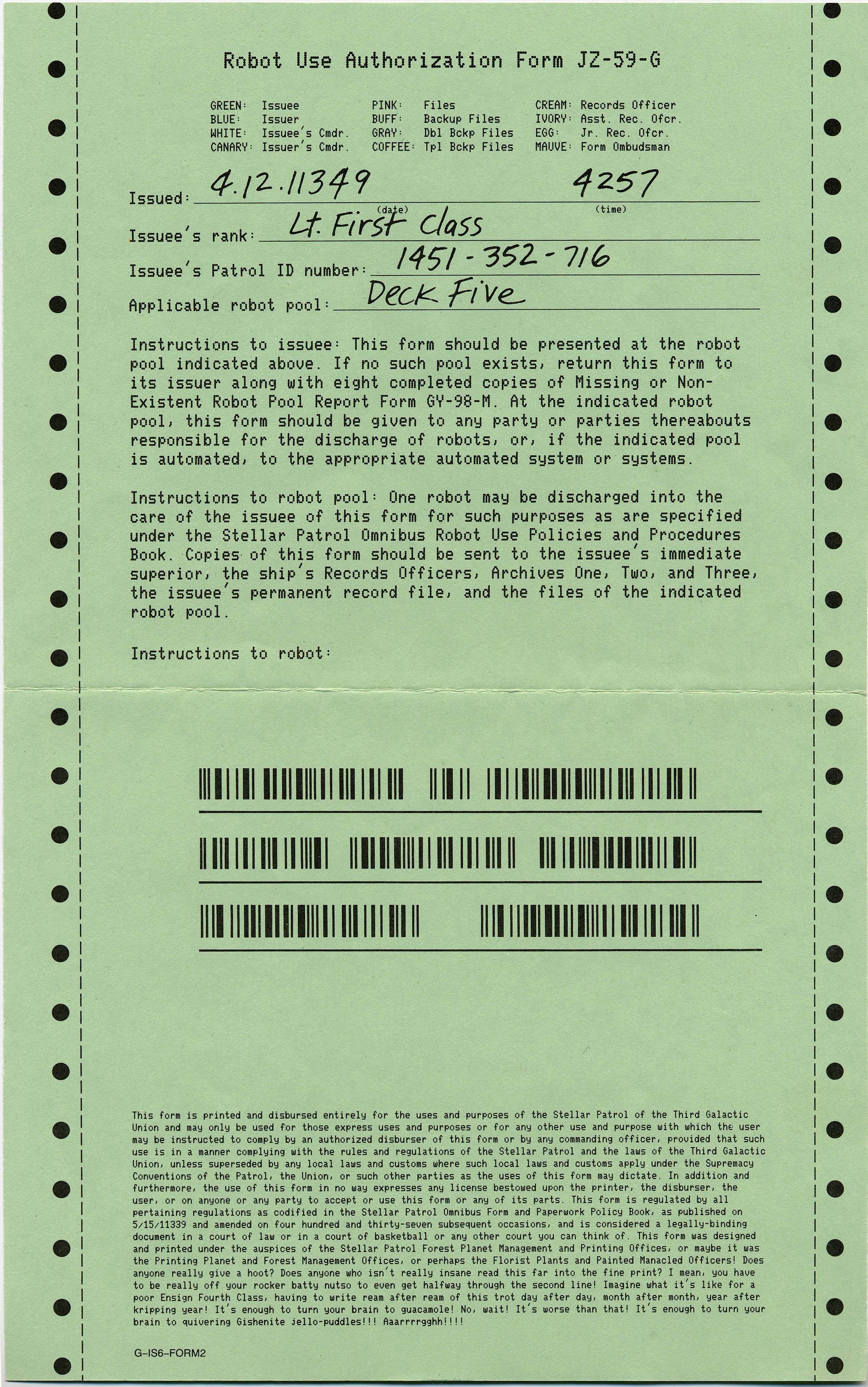

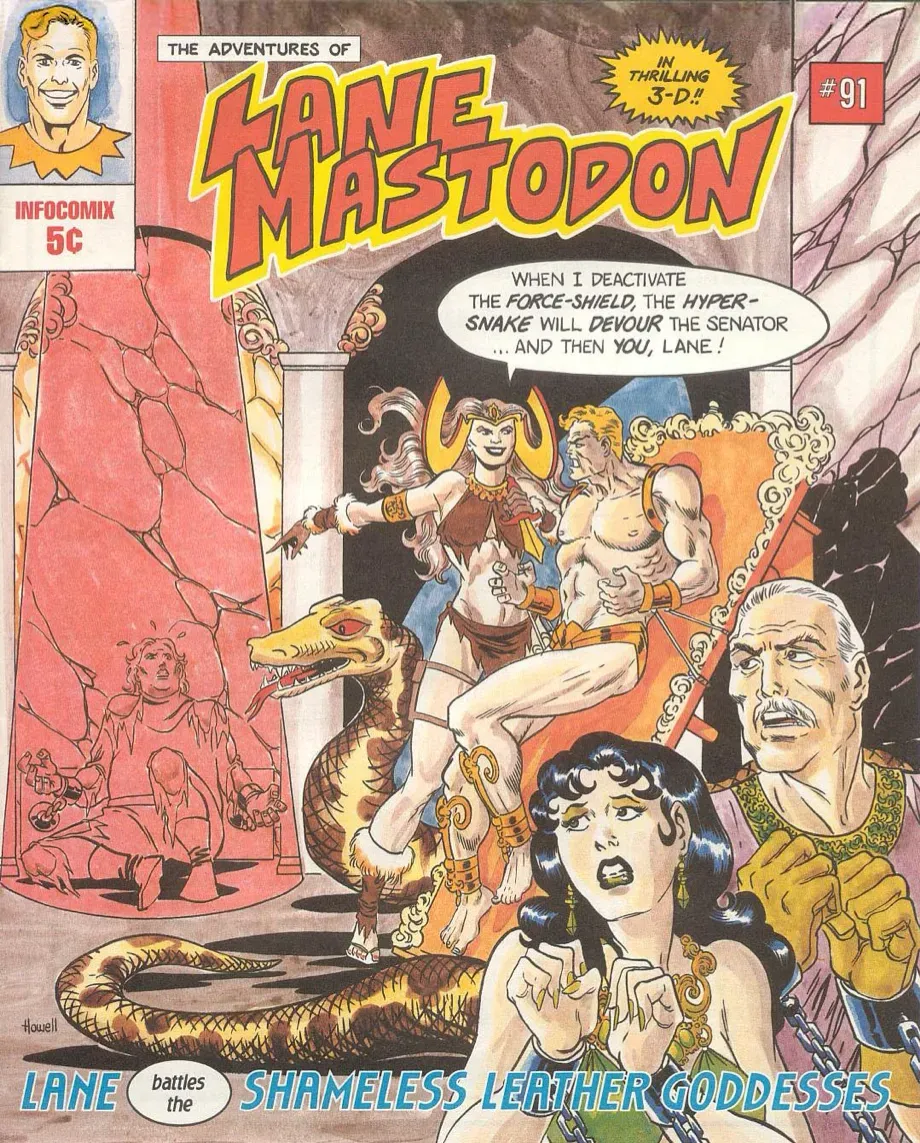

To help make up for these limitations [[footnote: And to add a bit of copy protection--these items often contained information critical to the games.]], Infocom (and other publishers of the time) embraced pack-ins called "feelies"--little tchotchkes and immersive booklets that drew the player into the game world before the floppy disk got anywhere near the drive. My favorites were the "Southland of Quendor" map and "The Lore and Legends of Quendor" book from Beyond Zork, and The Leather Goddesses of Phobos' [[footnote: This game wasn't the most age-appropriate, but I'll take that up with my therapist. It wasn't the worst thing I played on the Apple II. (That had an age verification quiz. I don't know how I got past those back in the day.)]] scratch and sniff card and 3D comic. I wish I still had the station blueprints, patch and forms from Stationfall. [[footnote: I mean, I wish I had all of these relics, but I can't blame my grade-school self for not knowing the nostalgia demon I would become. Technically they weren't even mine to hoard.]] The game doesn't loom large in my memory, but those feelies look like props from a Mothership game.

A limited selection of my favorite feelies. Images mostly taken, with thanks, from the Infocom Gallery.

Beyond Zork (1987)

"The horizon is lost in the glare of morning upon the Great Sea. You shield your eyes to sweep the shore below, where a village lies nestled beside a quiet cove. A stunted oak tree shades the inland road."

This was my first Zork game, and my first taste of interactive fiction.

I didn't realize it at the time, but this entry was unique in having ability scores, a rudimentary map and a combat system, making it the most overtly RPGish of all Infocom's games.

The significance of the default character name being "Frank Booth" was also lost on me. I couldn't find anything suggesting this was an intentional reference to David Lynch's "Blue Velvet," which had released the year before, but it'd be one hell of a coincidence [[footnote: I don't remember any nitrous-oxide tanks...]].

My dad was more of a sci-fi head, so we started this out as a duo but pretty quickly moved on. I did my best to continue on my own. It was slow going, but it was a lot of fun.

For fans of: "The Face in the Frost," by John Bellairs.

The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1984)

"As you part your curtains you see that it's a bright morning, the sun is shining, the birds are singing, the meadows are blooming, and a large yellow bulldozer is advancing on your home."

We got the babel fish!

Like I said, the old man was a sci-fi geek, so of course he'd read the books and watched the series on PBS, but this was 6-year-old me's first exposure to story, and the intergalactic utility of towels.

Watching the BBC series years later was surreal. I couldn't help but think of the series as the adaptation, not realizing that, of course, both were adaptations (or reimaginings)--and not even of the books, but of a radio series.

Plenty has been written about this game's puzzle design, and with good reason. Some of the ways you could dead-end yourself were truly cruel, but that just meant we had to dump more time into the game, so I wasn't complaining. Besides, we had no expectation of "fairness" in these games, we didn't know any better. If we couldn't figure something out, we put a pin in it and tried again later.

Eventually we did get ahold of some InvisiClues booklets, but they were used sparingly, and only as a last resort. Even then, the highlighted answers quickly faded away. At one point a friend of mine got caught up in the invisible-ink gimmick and revealed every single answer in the booklets we had, despite never having played the games. That’s how I learned the answers faded quickly once revealed—and that re-highlighting wouldn’t bring them back.

For fans of: ... I bet you can figure that out.

Leather Goddesses of Phobos (1986)

"Some material in this story may not be suitable for children, especially the parts involving sex, which no one should know anything about until reaching the age of eighteen (twenty-one in certain states). This story is also unsuitable for censors, members of the Moral Majority, and anyone else who thinks that sex is dirty rather than fun.

"The attitudes expressed and language used in this story are representative only of the views of the author, and in no way represent the views of Infocom, Inc. or its employees, many of whom are children, censors, and members of the Moral Majority. (But very few of whom, based on last year's Christmas Party, think that sex is dirty.)

"By now, all the folks who might be offended by LEATHER GODDESSES OF PHOBOS have whipped their disk out of their drive and, evidence in hand, are indignantly huffing toward their dealer, their lawyer, or their favorite repression-oriented politico. So... Hit the RETURN/ENTER key to begin!"

With the above warning screen displaying each time the game booted, exactly how The Leather Goddesses of Phobos was allowed into the rotation is beyond me.

Playing it again, I'm pretty sure he left it on "tame" mode and let the suggestive bits sail right over my head. The description of Trent splattering all over the walls did not sail over my head, though. It freaked me out despite all the previous fake-outs.

I remember the moment--though sadly devoid of context--when I realized the title was, I guess, risqué. I'd just said it out loud to an adult family member, then got the ineffable feeling that I shouldn't have done so. Maybe that moment is why this is the last Infocom game my dad and I played together.

For fans of: Amazing Stories, Barbarella, and, I don't know, Flesh Gordon?

The Lurking Horror (1987)

"This is a large room crammed with computer terminals, small computers, and printers. An exit leads south. Banners, posters, and signs festoon the walls. Most of the tables are covered with waste paper, old pizza boxes, and empty Coke cans. There are usually a lot of people here, but tonight it's almost deserted."

As a first attempt at pure solo play, The Lurking Horror threw me into the fire [[footnote: Or out into the blizzard.]]. It's arguably even more age-inappropriate than Leather Goddesses of Phobos, albeit for very different reasons. The latter's vaguely phallic cover art and "mature" humor were lost on me at that age, but this game scared the hell out of me. There's a real sense of isolation and dread throughout, resulting in something like text-based survival horror [[footnote: Come to think of it, with its focus on resource constraints and attrition, survival horror is another genre that overlaps with OSR play.]].

It was my first real exposure to Lovecraftian horror [[footnote: Any horror, unless you count "Bunnicula: A Rabbit-Tale of Mystery." I don't.]], and some of the fates that can befall the player character were truly disturbing [[footnote: One word: Rats.]]. Up way past my bedtime, all by myself.

For fans of: H.P. Lovecraft, obviously, but this time around the early dream sequence reminded me of "Creep, Shadow!" by A. Merritt.

"You are at the bottom of a seemingly endless stair, winding its way upward beyond your vision."

I've heard that when you have a kid, you get to experience childhood again through them. You introduce them to the things you enjoyed, and watch it hopefully spark joy, and you feel it. I believe this was especially true for my dad. He was never the most social guy, and few of his friends shared his geekier interests. He introduced me to comics [[footnote: The standards from Marvel and DC, including all things Conan.]] and movies [[footnote: "Blade Runner," "The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension," "Cherry 2000." Only the very best 😬. "Conan the Barbarian," too, but he always griped Arnold being miscast.]], then we discovered these games together. When I showed a lasting interest he started relating to me as a friend--albeit one with a strict bedtime, and the reading comprehension of a grade schooler. For better or worse he had someone to share these things with, even if the content wasn't always age-appropriate. A more generous and equally likely explanation is the inverse: He wanted to be someone I could share these interests and experiences with--someone his dad never was for him.

If you were somehow inspired to experience (endure?) any of these ancient relics, you can paste game file URLs from The Obsessively Complete Infocom Catalog into Parchment and play in your browser. Or download the files to play with Frotz, if you prefer (as I do) to keep it local.